"La Guardia Nueva" (The New Guard) period lasted from approximately 1925 to 1935. The new musicians developing during this period would be known as "The 1925 Generation."

This period saw:

- Introduction of "El Cuatro" The Four

- Julio de Caro introduce a new style

- Tango for dancers decline

- Tango become a popular subject for films

- Tango performed live on the radio

- The introduction of quality microphones.

El Cuatro (The Four)

During this period, the habanera influence began to fade and the tempo of the music slowed down. In "Tango: The Art History of Love," tango guitarist Ubaldo de Lío says, "The earliest form of tango was a type of habanera. The tango-milonga then followed. After that came 'the four,' four quarter-notes per measure. We still ask ourselves who invented 'the four.' Some say Canaro, others say Firpo, a few claim de Caro." "The four" consists of 4 equal quarter notes (beats) with 2 strong beats (down beats) and 2 weak beats (up beats). In dancing, we usually step on beats 1 and 3 (the down beats) and not 2 and 4 (the up beats) unless we using traspíe or double-timing.

From Robert Farris Thompson's "Tango: The Art History of Love:"

"The four" arrived in force in the 1920s, with Firpo, Canaro, and de Caro. Important changes in harmony and phrasing came with it: polyphony and counterpoint emerged with de Caro. Tango was in a state of creative ferment. Black swing and black imporvisatin met innovations evolving within the Western-oriented tradition. The black composer Mendizábal, we recall, had designed the early structure of tango, involving a first and third part of sixteen bars each with a bridge of thirty-two bars in between. Now de Caro and his peers swept this away: 'After 1925 nobody writes [tangos] in three parts any more; sometimes introductions, bridge passages, and codas are added.' The trend was now to structure in two parts, doubled in execution: A B A B.

In the late 20s and early 30s, more classically trained musicians began to join and form orchestras and were influencing the largely self-taught musicians of the previous generation. Some of the older generation would say things such as "They have turned tango into church music," because they were working more with melody and harmony than rhythm.

Julio de Caro

Julio de Caro

The most famous of these was the violinist Julio de Caro who put together an orchestra which included the bandoneonista Pedro Laurenz. He still retained an element of tango's street beginnings, but with more elegance and complex structure. He also slowed tango down even more. This new style combined with Tango Cancíon and the popularity of records meant that a larger "listening" audience was growing rather than a "dancing" audience. Orchestras no longer had to depend on dancers to pay the bills and began creating music that was not popular with dancers and tango as a dance sharply declined.

After this period, most orchestras were from one of two camps, the traditionalists or evolutionists. The traditionalists would consist of orchestras such as Francisco Canaro, Juan D'Arienzo, Edgardo Donato and Rodolfo Biagi. The evolutionists would consist of orchestras such as of Osvaldo Pugliese, Aníbal Troilo, Carlos di Sarli, Osvaldo Fresedo and Pedro Laurenz. Not that the traditionalists did not evolve as well, they just did not take it as far.

With the advent of silent films, the best tango musicians were sought after to play for the movies. For less popular films, one pianist would do, but for more popular films sometimes a trio, quartet or a sexteto típico would be employed.

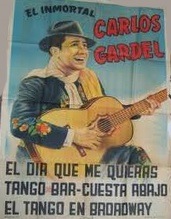

Tangos were also a popular subject for films and the tango stars of the day, including Gardel, often starred or made appearances in them.

Tangos were also a popular subject for films and the tango stars of the day, including Gardel, often starred or made appearances in them.

Tango orchestras were also very much in demand for the new medium of radio and would often play live and have their own weekly shows.

In the 1910s, as orchestras became more in demand to play large dances and festivals, their sizes ballooned to more than 1 dozen musicians. For a festival in 1921, Francisco Canaro presented an orchestra of 12 bandoneons, 12 violins, 2 cellos, 2 double-basses, 2 pianos, 1 flute and 1 clarinet. By the mid-1920s, the popularity of the microphone had made it so that most orchestras took the form of sextetos típicos.

Lorenzo by Julio de Caro con Luis Diaz (1926)

Amurado by Juan Felix Maglio (1927)

Flores Negras by Julio de Caro (1927)

Adios Muchachos by Orquesta Tipica Victor (1927)

Viejo Ciego by Francisco Canaro (1928)

Quejas de Bandoneon by Roberto Firpo (1928)

Felicia by Edgardo Donato (1930)

Fruta Prohibida by Orquesta Tipicia Brunswick (1931)

El Huracan by Edgardo Donato (1932)

Milonga Sentimental by Francisco Canaro (1933)

Ventarron by Orquesta Tipica Victor (1933)

Vida Mia by Osvaldo Fresedo (1933)

Siempre es Carnaval (1934)

Poema by Francisco Canaro (1935)